Peredachi: A Public Project in Support of Political Prisoners

- Feb 4, 2021

- 6 min read

Updated: Aug 12, 2024

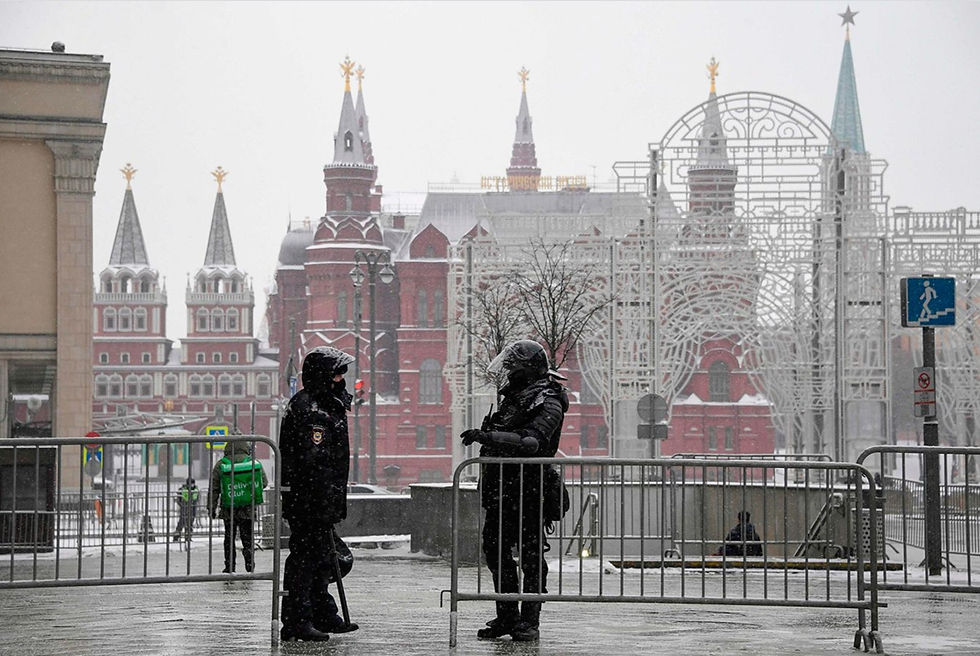

Photo by Александр Неменов (Aleksandr Nemenov) / AFP / Scanpix / LETA

Peredachi is an ongoing public project conducted by volunteers all over the globe in support of the detained political protesters in Russia. Volunteers locate missing detained protesters and arrange deliveries of food, water, toiletries, medicine, and legal help to them, which marginally improves the horrendous conditions in which they are being kept. This project emerged in 2017 through the efforts of the 20-year-old journalist Liza Nesterova in response to the Russian police's tendency of concealing information regarding political prisoners. It grew in January and February of 2021 due to Russia's recent mass protests and arrests.

A Brief Summary of the Protests:

The initial protests were held in response to the politically-motivated arrest of Vladimir Putin’s opposition leader Alexei Navalny as well as to the widespread corruption by which contemporary Russia is characterized. Navalny had been poisoned with a nerve agent Novichok in August of 2020. To get treatment for this attack, he was transferred to a hospital in Germany, where he spent the following five months recovering. While there, an investigation into his asassination attempt was conducted by Navalny himself and Bellingcat, an investigative journalism team, which concluded that the attempt was made on government orders (all of the videos below have synchronous English subtitles that can be turned on in the videos’ settings).

Later, Navalny called one of his would-be murderers and even got him to confess.

He returned to Russia on January 17th and was arrested right at the airport, which prompted the first round of protests. Immediately, his team released a video of an investigation into Putin’s ridiculously elaborate home, at which point the protests grew.

The uncovering of the palace occurred mere months after the Russian government updated the minimum amount of money that it is considered a Russian citizen can live on, which totals to 11 653 rubles per month or roughly $153.45 USD and $196.43 CAD. So, with much of the country living below the poverty line, Vladimir Putin used the taxpayers’ money to build himself a palace that is estimated to cost $1.3 Billion USD.

Following Navalny’s arrest and the well-timed release of the Putin’s Palace video, thousands of protesters took to the streets of Russian cities, protesting both the opposition leader’s arrest and the corruption that had been uncovered. These protests have continued since then and have been responded to by Russian police with beatings and mass arrests. Some photos from the protests:

The detained protesters were often subjected to torture and were refused food, water, and adequate living conditions for hours that stretched into days. Due to the overflow of people in detention centers, some were kept in transport vehicles for tens of hours, parked in temperatures that dropped below -20°C with the engines turned off. Some have reported being tortured, with one woman recalling police officers placing a bag over her head and beating her up, with others reporting police officers breaking their limbs and refusing to arrange medical help afterward.

Once processed into detention centers, the detained protesters were often refused food, water, and medicine. Some detainees resorted to melting and drinking snow. Their phones were seized and they were not allowed to contact their relatives or lawyers. A look inside some of the detention cells:

On February 2nd Navalny was sentenced to a prison term of two years and eight months for violating the terms of his probation that was related to a case that has been confirmed by the European Court of Human Rights as politically-motivated. The court did not take into account that the probation was violated due to him being in a coma after a failed attempt at his life. This ruling has prompted more protests and mass arrests.

Peredachi

Following the mass arrests, an ongoing initiative was developed called “Peredachi” (Передачи), which, in Russian, has the two-fold meaning of “Deliveries” and “Broadcasting”. This initiative seeks to locate all of the arrested protesters and arrange deliveries of food, water, toiletries, medicine, and legal help to them.

The deliveries were coordinated through Telegram, a messaging software, with the efforts of volunteers all over the globe. To track the detainees, we, the coordinators of Peredachi, used information from OVD INFO, an independent human rights project that, among other initiatives, keeps track of politically-motivated detentions in Russia and provides and coordinates legal assistance for them. This agency provided us with a base of information regarding the whereabouts of the detained protesters, which we synthesized into Excel spreadsheets, but this information was often outdated due to the protesters frequently being moved around between police stations, detention facilities, and courts, of all of which there are many locations.

Locating detainees was difficult due to Russian police typically only giving information regarding detainees' whereabouts to their relatives. Still, due to our recruitment of detainees' relatives and organization of their information, we were able to locate a substantial amount of detainees all over Moscow, allowing us to continually update our databases. Creating these databases was essential, because deliveries of any kind to Russian detention centers can only be made to specific people, which requires knowing a detainee’s full name and precise detention center. In any case, those were the rules when we began coordinating these deliveries. In a matter of days, new rules such as having to know the detainee’s cell number, all deliveries being in transparent bags, and only one delivery per person being allowed, emerged. The situation was constantly changing due to the barriers that the police system kept putting up for us, but, due to the large number of volunteers that reached out to support this project, we were able to mobilize a lot of people to frequently update our databases and arrange efficient deliveries. Using Telegram and Excel spreadsheets we were able to designate these deliveries among the Moscow volunteers, many of whom have been successful in delivering many essentials to the detainees, and, with the help of OVD INFO, provide them with legal help. As well, these databases allowed us to help those people that reached out to us in search of their relatives when the police refused to help them with this.

Aside from satisfying a desire for action against Russia’s oppressive regime, this project restored my faith in the strength of the Russian people. I emigrated from Russia when I was ten years old, and, to the questions of whether I ever go back, I used to answer that I do, because I have many relatives there, but I typically hate being there. The atmosphere of contemporary Russia is difficult to describe, but to me it has always seemed cold and hostile. Throughout the past eleven years that I have spent living in Canada, I have felt a wide range of feelings toward my homeland, most of which have been those of guilt, anger, and resentment. Now, for the first time, I can add the feeling of hope to this list.

The number of people that have been coming out to protest as well as the number of arrests made by the police are both record-shattering. Russia has not seen protests of this size since the Soviet times and this amount of arrests (over 5,500 at the time of writing) ever. Some of the protesters are coming out to protest for the very first time, if not in support of Navalny per se, then in protest against the overall corruption that has been uncovered by his team. The combination of Navalny’s arrest, the revealing of Putin’s palace, and, perhaps, the energy saved up over nearly a year spent largely inside, has resulted in the biggest public outcry Russia has seen in decades. The people are furious and the government is afraid.

As well, the sheer number of Russian volunteers that have reached out to be instrumental in this project, be it to contribute financially or stand for hours in Russia’s cold to attempt to deliver a gallon of water to the detainees, is astounding. At the time of writing, the main Telegram channel for coordinating deliveries has nearly 7,500 members, and that number is growing. Several times per hour, a new volunteer emerges stating that they are furious and want to help in any way that they can, at which point we, the coordinators, give them a specific task, or direct them to a coordinator that is in the process of arranging phone calls to detention centers to continue updating our databases, or to a coordinator arranging deliveries, etc. Right after mobilizing a team of people to update databases with names, we contact volunteers in Moscow that are on standby with deliveries and tell them “quickly, there’s this person in this cell of this detention center, can you get to them?” and they are able to make a delivery happen to a person who’s been hungry for hours if not days. When a package is delivered, we cheer along with the volunteers in Moscow. We are tired - some volunteers coordinate deliveries for as long as 15 straight hours at a time, but we are hopeful. The Russian police may have batons and tear gas, but we have Telegram and Excel.

Photo by: Валентин Егоршин (Valentin Egorshin) / AP / Scanpix / LETA

Comments