Essay on The War on Drugs

- savelasya

- Dec 25, 2021

- 10 min read

In this paper I plan to examine the War on Drugs, its effects on incarceration rates in the U.S.A., and the incarceration rates’ inequality. I will begin with a history of the War on Drugs, and explain why it is inherently ineffective. I will be using the theory of the Balloon Effect to make this point. I will then explain how the War on Drugs contributes to the rise in incarceration rates by considering the U.S.’ incarceration rates from the beginning of the war to the present day. Finally, I will point out that different races are disproportionately incarcerated and will conclude that the War on Drugs is discriminative toward minorities. The War on Drugs has a lengthy history that has been unravelling throughout the last one hundred years. In its beginning, “[p]rotestant missionaries from the U.S. working in China and other American religious groups joined with temperance organizations in convincing Congress that drugs were evil and that drug users were dangerous, immoral people” (McNamara, 2011:98). Thus, drugs and people who use them have been portrayed as public enemies, and the focus has been on the elimination of drug use and punitive measures for their users. This approach has resulted in a lengthy war against drug users that has involved various policy changes, all targeted at the complete eradication of drug use. As McNamara writes, “[i]n 1914, a government publicly advocating the reduction of crime passed legislation creating unknown millions of additional crimes. Overnight, the U.S. government turned hundreds of thousands of previously law-abiding drug users, ex post facto, into criminals. (McNamara, 2011:99)” Though drug use was of concern as early as the 1910s, it ramped up significantly in the middle of the century. The war on drugs accelerated in 1951, when president “Truman backed the Boggs Act of 1951, a little piece of legislation that turned out to have big consequences” (Crandall, 2020:134), which aimed to reduce drug use and addiction and “was the first federal law to require mandatory sentences for drug convictions” (Crandall, 2020:134. President Eisenhower, who succeeded Truman, was also set on reducing drug use and addiction and pledged to wage a war on drugs. He “convened a special cabinet committee to coordinate a national anti-narcotics initiative; its mandate was to run a ‘national survey of both addiction and law enforcement needs.’ Two years later, he signed a bill that authorized treatment of regular opiate users in the District of Columbia” (Crandall, 2020:135). This bill was a step toward focusing on treatment as opposed to punitive measures when it came to drug use, but “drug trafficking and use as well as addiction rates continued to rise through the late 1950s” (Crandall, 2020:135) nevertheless. Harry J. Anslinger, who was the first commissioner of the U.S.’ Treasury’s Department’s Federal Bureau of Narcotics, “assured the White House and Capitol Hill that the solution lay in one direction: tougher mandatory sentences” (Crandall, 2020:135), which caused the government to once again focus on punitive measures instead of treatment. Then, in 161, the United Nations “passed the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs … [, which] codified many prior international treaties and extended existing bans to include the cultivation of plants grown as the raw material for drugs” (Crandall, 2020:135). The purpose of this convention was combating drug use through unified international efforts, and “two forms of intervention and control that work together. First, it seeks to limit the possession, use, trade in, distribution, import, export, manufacture and production of drugs exclusively to medical and scientific purposes. Second, it combats drug trafficking through international cooperation to deter and discourage drug traffickers” (unodc.org). In 1962, president Kennedy firstly introduced the two-day seminar, the White House Conference on Narcotics and Drug Abuse, and in “1969, President Richard M. Nixon announced with much fanfare his “national attack on narcotics abuse.” (Crandall, 2020:139). In 1968 president Johnson “reinforced the status of narcotics as a law-enforcement concern when, by executive order, he created the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, transferring all administrative responsibility for drug law from the Departments of the Treasury and Health, Education, and Welfare to the Department of Justice.” (Crandall, 2020:136). An important event in the drug war was in 1970 when “Nixon signed the Comprehensive Drug Abuse and Control Act” (Crandall, 2020:141), which sorted all drugs into schedules based on perceived severity and assigned corresponding punitive measures to each. Following that, in 1973, Nixon introduced the Drug Enforcement Agency, a federal initiative aimed specifically at combating drug use in more severe ways than before and on a bigger scale, extending into other countries. In spite of all of the aforementioned efforts, drug use did not decrease throughout the 1970s and “juvenile arrests for drug possession had surged by 800 percent between 1960 and 1967” (Crandall, 2020:139-140) and “the heroin epidemic peaked in the mid-1970s” (Crandall, 2020:150), which indicates that the War on Drugs was and continues to be a failure. To begin exploring the reasons for which the War on Drugs is inherently ineffective, it is important to consider the theory of the Balloon Effect. The Balloon Effect uses a balloon to represent the way in which the U.S. enacts its drug policies. As explained by Windle and Farrell, “[i]n the metaphor, the size of the balloon is the size of the illicit drug trade, the volume of air is the volume of illicit drug production, and pressure on the balloon is from law enforcement. When one part of the balloon is pushed, it expands elsewhere to an equal extent. There is no net reduction in total air, so it is a hydraulic model” (Windle & Farrell, 2012:868). Even though the U.S. law enforcement might shut down many drug operations, since the demand for drugs does not reduce, more operations will emerge to meet this demand, but will likely be more dangerous or involve international schemes, actually causing drug producers and traffickers to become more skilled at concealing, trafficking, and supplying their products. As well, as McNamara writes, “the illegality of certain drugs inflates their price and may well lead some individuals to commit crimes to obtain drugs” (McNamara, 2011:108). Labelling drugs as illegal and attaching punitive consequences to them without decreasing the demand for them leads to an increase in both the drug prices and drug-related crimes. Thus, according to the Balloon Effect, since the demand for drugs is not reduced, drug operations will continue to emerge even while many are shut down by the government, because the net demand for drugs remains unchanged due to the kind of product that drugs are. Therefore, the approach of the War on Drugs is inherently incorrect and has failed to reduce the consumption of drugs in the U.S.

Having established the War on Drugs as inherently ineffective, it is now important to examine some of its consequences prior to examining drug-related incarceration rates so as to be able to place them in context. The costs of the War on Drugs in the U.S. are approximated by McNamara in his article. He writes that “[i]n 1972 … the federal drug war budget was roughly $101 million. In 2011 President Obama’s requested budget for “Federal Drug Control” is a record $15.5 billion” (McNamara, 2011:106), which indicates a colossal increase in less than four decades. As well, “the states are estimated to have spent at least $30 billion each year on justice-related drug war expenses since 1998” (McNamara, 2011:106), resulting in $690 billion spent on the drug war since that year. The budget of the DEA alone had “an annual budget of $75 million; in 2016, those figures were, respectively, 5,000 agents and $2.7 billion” (Crandall, 2020:149). The budget of the drug war has thus continuously been increasing since its beginning and has become a very considerable part of the federal budget. Drug-related arrests and incarceration rates have also gone up significantly since the beginning of the War on Drugs. “In 2008, The Federal Bureau of Investigation reported a total of 14,005,615 arrests in the United States. The number of arrests made by American law enforcement officers in that year for drug abuse violations was 1,702,527 (12% of all arrests) and was more numerous than for any other crime” (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2009). These statistics illustrate the U.S.’ strategy of focusing on punitive measures when it comes to drug use, but “jailing drug users does not persistently lessen drug use in society at large, or for that matter in prisons themselves, where illegal drugs are available. Incarceration for mostly minor drug offenses usually destroys the person’s life and does immense harm to families and neighborhoods” (McNamara, 108). The War on Drugs has thus increased arrests and incarceration, which has long-lasting detrimental effects on the incarcerated people, but, due to the Balloon Effect, has not actually lessened drug use. Mukku et al, in their article Overview of Substance Use Disorders and Incarceration of African American Males write that “[t]he high rate of incarceration in U.S. may adversely affect health care, the economy of the country, and will become a burden on society (Mukku et al, 2012:1), concurring with the notion that increasing incarceration is a very ineffective way of dealing with drug use. Therefore, the War on Drugs has drastically increased federal spending and arrests.

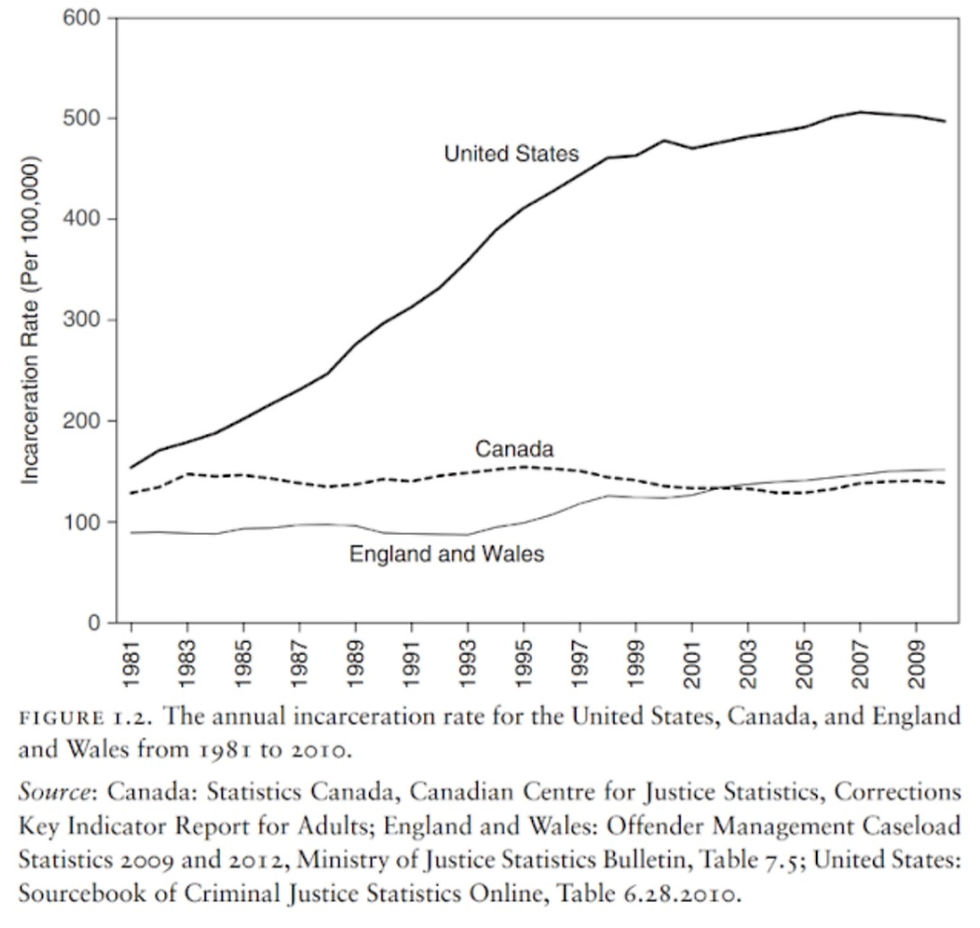

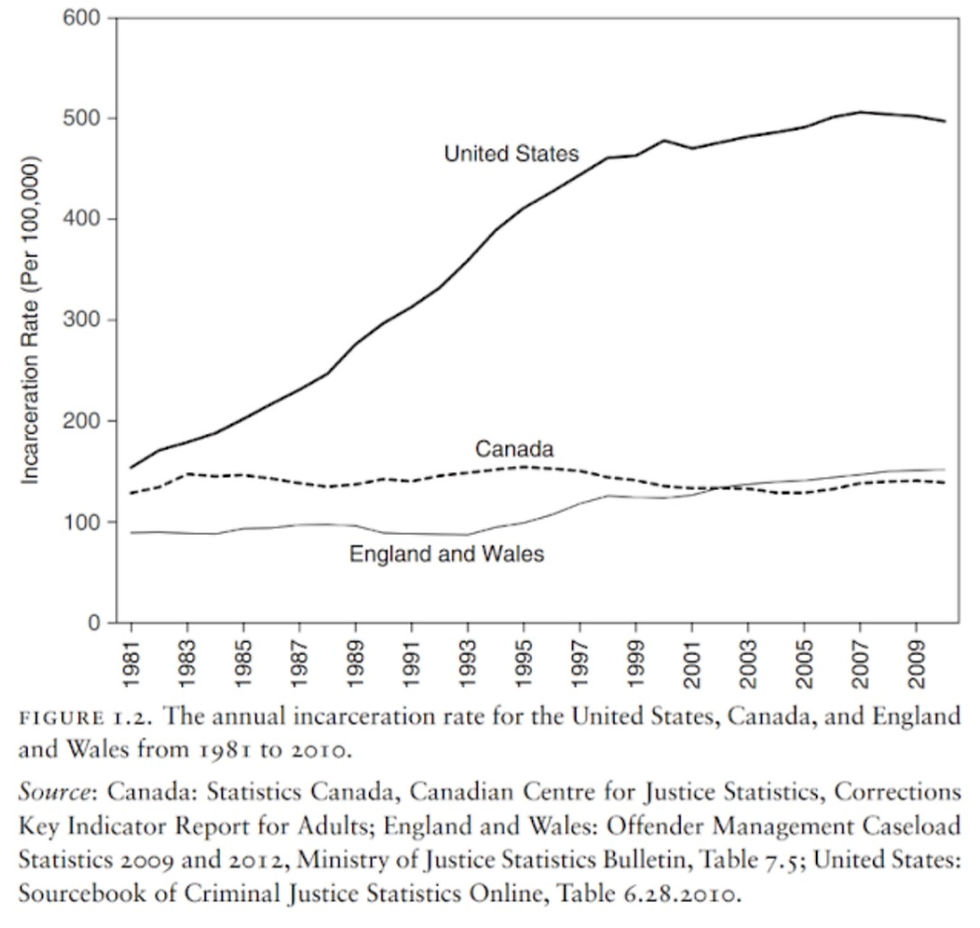

It is now important to examine incarceration rate trends since its beginning. Incarceration rates in the United States have grown dramatically since the beginning of the War on Drugs. As Peter K. Enns writes in his book Incarceration Nation: How the United States Became the Most Punitive Democracy in the World, “the United States hands down longer sentences, spends more money on prisons, and executes more of its citizens than every other advanced industrial democracy” (Enns, 2016:3). The following graphs illustrate the rise of U.S. incarceration rates as compared to other countries:

As these graphs illustrate, the U.S.’ rates of incarceration began to rise significantly in the late 1970s and surpassed those of other democracies. Though they’ve begun to level out, they are still significantly higher than those of other countries, and can partially be explained by the War on Drugs. Having established incarceration rates as having risen drastically due to the War on Drugs, it is now important to examine the ways in which they, and, by extension, the efforts of the war are discriminative. In his journal article Race, Class, and the Development of Criminal Justice Policy, Marc Mauer outlines the disproportionate amounts of drug-related incarceration that are experienced by marginalized communities due to the focus on punitive measures where drugs are concerned. He writes that “in well-to-do communities, drug abuse is primarily addressed as a social or health problem, and there is no shortage of treatment resources for those with the means to pay. But in low-income communities, those resources are in limited supply, and a criminal justice response—arrest, prosecution, and incarceration—becomes far more likely.” (Mauer, 2004:85). This difference in treatment of people who use drugs indicates that marginalized communities experience systemic punishments in ways that members of well-to-do communities do not. As a result, “one of every eight black males in the 25–34 age group is locked up on any given day and 32% of black males born today can expect to spend time in a state or federal prison if current trends continue” (Mauer, 2004:79). Spending time in a prison significantly restricts one’s opportunities such as employability and approval for bank loans. Systemically incarcerating more marginalized people who use drugs than white people who use drugs results in marginalized people getting significantly less opportunities and could actually contribute to them to reverting to drug habits or illegal activities. Where white people who use drugs get opportunities for rehabilitation and the focus is on their health, marginalized people experience punitive measures for the same and lesser offenses. As well, “[i]n recent years, the racial dynamics of the drug war have played themselves out most prominently in the punishments meted out to crack cocaine offenders” (Mauer, 2004:83), writes Mauer. Though cocaine and crack cocaine are very similar substances, cocaine is treated as a much better drug than crack cocaine is. Cocaine is typically associated with white, well-off people who use drugs, whereas crack cocaine is associated with marginalized people who use drugs. As a result, “[f]or crack, the possession or sale of as little as five grams mandates five years in federal prison, but for cocaine that penalty is not triggered until the sale of one hundred times that amount, or five hundred grams. The racial disparities that have accompanied the prosecution and sentencing of federal crack offenders have been dramatic, with African Americans constituting 85% of defendants each year” (Mauer, 2004:84). This statistic points to more disparities in the treatment of marginalized people who use drugs, since they are vastly overrepresented in drug-related offences. Mukku et al, which concur with Mauer in that “[t]here has been an unprecedented increase in incarceration among African American males since 1970” (Mukku et al, 2012:1), also point out that “Hispanics and Native Americans are also alarmingly overrepresented in the criminal justice system” (Mukku et al, 2012:3). Mauer also points out geographic racial disparities by noting that various states have “enhanced penalties for selling drugs near a school zone” (Mauer, 2004:84). “Since large sections of urban areas are within 1,000 feet of a school zone, arrestees in those areas—disproportionately black and brown—are far more likely to be affected by these penalties than their white suburban counterparts” (Mauer, 2004:84), writes Mauer. As a result, “[a] recent examination of juveniles waived to adult court in Chicago for school zone transactions revealed that fully 99% of the cases—390 out of 393—were African American and Latino teenagers (Mauer, 2004:84). Such a large number of school zone transaction cases is far from representative of the general population, indicating that the laws that result in it, as well as the entire approach to curbing drug use, is discriminatory. The States thus pass laws that are discriminatory to minorities, disproportionately arrest minorities, and incarcerate them more frequently than they do white people. The U.S.’ War on Drugs and its premise to completely eradicate drug supplies and usage have been a complete failure and have done nothing to decrease drug use. Instead, the drug war has caused drug manufacturers and traffickers to become more skilled and has made the conditions in which drugs are produced and supplied more dangerous. Despite various proof of failure that stretches across many decades, the strategy of the War on Drugs has remained unchanged. Since its conception it has resulted in mass national spending and arrest and incarceration rates well beyond those of any other democracy. The arrests and incarcerations do little to combat drug use, which is common in prisons and the demand for which remains unchanged, but actually creates barriers for people with previous offenses. Furthermore, the arrests and incarcerations are not representative of the U.S. population, with the majority of arrested and incarcerated people being minorities. Thus, the War on Drugs has not only failed to combat drug use, it has actually reinstilled systemic inequalities already ravaging the U.S.

Works Cited: Crandall, Russell. Drugs and Thugs: the History and Future of America's War on Drugs. Yale University Press, 2020.

Enns, Peter. Incarceration Nation: How the United States Became the Most Punitive Democracy in the World. Cambridge University Press, 2016. Mauer, Marc. “Race, Class, and the Development of Criminal Justice Policy1.” Review of Policy Research, vol. 21, no. 1, 2004, pp. 79–92., doi:10.1111/j.1541-1338.2004.00059.x. McNamara, Joseph D. “The Hidden Costs of America’s War on Drugs.” The Journal of Private Enterprise, vol. 26, no. 2, 2011, pp. 97-115 Mukku, Venkata K., et al. “Overview of Substance Use Disorders and Incarceration of African American Males.” Frontiers in Psychiatry, vol. 3, 2012, doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2012.00098. “Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs.” United Nations : Office on Drugs and Crime, www.unodc.org/unodc/en/treaties/single-convention.html?ref=menuside.

Windle, James, and Graham Farrell. “Popping the Balloon Effect: Assessing Drug Law Enforcement in Terms of Displacement, Diffusion, and the Containment Hypothesis.” Substanzace Use & Misuse, vol. 47, no. 8-9, 2012, pp. 868–876., doi:10.3109/10826084.2012.663274.

Comments