A World Upside Down: Mapping a Sense of Belonging on UBC Campus Before and After October 7th, 2023

- savelasya

- Jan 4, 2025

- 19 min read

Updated: Jan 21, 2025

A World Upside Down: Mapping a Sense of Belonging on UBC Campus Before and After October 7th, 2023 Introduction

Following the Hamas-led October 7th, 2023 attack on Israel and Israel’s subsequent retaliation on Gaza, campuses across Canada experienced deep ideological divides. As antisemitic hate crimes grew throughout the country (Baxter, 2024), so did hostility toward UBC students who supported Israel. Hostile incidents mounted on campus and included regular anti-Israel demonstrations (Chaudhry, 2024), a pig’s head being speared on a university gate (Little and Lazatin, 2024), a university building being vandalized and defaced with anti-Israel slogans (Ruttle, 2024), and attempts to remove Hillel House - the center of Jewish campus life - from campus (Little, 2024), among others. Suddenly finding themselves in an environment of pervasive hostility and in which their opinions were disparaged, many Jewish, Israeli, and Zionist students experienced a severely decreased sense of belonging on campus.

Adin Mauer*, an Israeli-Canadian UBC student, was one of several students who left for Israel once news of the attack broke. In what should have been the final year of his Computer Engineering degree, he put his studies on hold to support his home country. He would come back to an almost unrecognizable campus, where “everything was upside down”, as he would later describe it. He himself became a target of protests when he came to Hillel House to give a talk on his experience in the army. As his talk was going on, protesters gathered and chanted outside of the building and even disrupted the event inside of it (Rochefort, 2024). What followed was a hate campaign against him, in which people spread flyers over the campus vilifying him, students took pictures and recordings of him on campus, and professors alluded to him as a danger for Arab students. On a personal level, it resulted in high levels of isolation and hostility, as his friends and professors stopped talking to him. All of this severely impacted Adin and shattered his sense of belonging at UBC. To capture Adin’s altered perception of the campus, I asked him to engage in a social mapping exercise. His task was to map his sense of belonging at UBC before and after October 7th, 2023.

*Many details included in this piece make Adin identifiable, due to the public nature of some of the incidents that have taken place. Anticipating this, I informed Adin of this possibility in case it changed his willingness to participate in the project, but it did not. Further, he asked for his real name to be used in the paper.

Belonging

In this paper, I lean on definitions of belonging provided by Nira Yuval-Davis in her 2006 article Belonging and the Politics of Belonging. Yuval-Davis writes that “[b]elonging is about emotional attachment, about feeling ‘at home’ and, as Michael Ignatieff points out, about feeling ‘safe’” (Yuval-Davis, 197). Emotional attachment in connection with a sense of belonging resonated deeply with Adin, as he attributed strong emotions to his feelings of belonging and non-belonging. The feeling of belonging also became closely linked with a feeling of safety. As his sense of safety on campus decreased, so did his sense of belonging, reflecting the close and causal relationship between the two.

Belonging also emerges as a dynamic and fluid process. Yuval-Davis writes that “[p]eople can ‘belong’ in many different ways and to many different objects of attachments. These can vary from a particular person to the whole of humanity, in a concrete or abstract way; belonging can be an act of self-identification or identification by others, in a stable, contested or transient way. Even in its most stable ‘primordial’ forms, however, belonging is always a dynamic process, not a reified fixity, which is only a naturalized construction of a particular hegemonic form of power relations” (Yuval-Davis, 199). This multiple, dynamic understanding of belonging rang true for Adin. For him, belonging is closely related to his self-identification as well as his identification by others. His sense of belonging was immensely influenced by external, dynamic events, which in turn made his experience of belonging dynamic in itself. He was also able to navigate his diminished sense of belonging by developing that sense in relation to other spaces and groups, demonstrating adaptability and revealing belonging to be an ever-changing process.

Social Mapping

Social mapping is a tool used to capture various subjectivities of space. A researcher asks research participants to draw maps that illustrate a specific sense or relationship they have to a particular space. The maps vary immensely and can be realistic or abstract, and depict a space in its entirety or focus on only some of its aspects. The visual illustrations, which are often paired with interviews or stories of the participants, can be used to demonstrate these individuals’ experiences and identify and advocate for necessary changes. These illustrations have the potential to be particularly compelling, as what often emerges from them are powerful visual depictions of experiences, along with persuasive personal stories.

In his chapter of Out in Public: Reinventing Lesbian/Gay Anthropology in a Globalizing World, titled Professional Baseball, Urban Restructuring, and (Changing) Gay Geographies in Washington, DC, anthropologist William L. Leap engaged in “mapping gay city”. Leap “asked DC-area gay men to “draw a map of Washington, DC as a gay city,” (Leap, 205) to explore “how the discursive construction of a moral geography … strengthens connections between (homo)sexual privilege and the goals of urban planning, at the expense of urban residents whose lives are disrupted by restructuring agendas” (Leap, 202). In capturing gay Washington residents’ perceptions and uses of space, Leap is able to demonstrate how their experiences intersect with proposed urban planning projects that may not take their needs into account. Intriguingly, Leap pays attention not only to what is drawn, but also to what is missing, the “empty white space.” (Leap, 208). Discussing a map with a lot of its space left empty, he writes that “one of the ways in which Robbie’s gay city map reconfigures the conventional mapping of DC geography is through this blanket deletion of sites. Other elements that help achieve this reconfigured display include decentralization, spatial separation, and distance” (Leap, 208). Space left intentionally empty can communicate something distinct about an individual’s experiences. In Robbie’s case, as Leap explains, the “blanket deletion of sites” (Leap, 208) conveys these sites’ irrelevancy for him. Overall, Leap’s project reveals the perspectives of various gay Washington residents in terms of how they use urban space in a very compelling visual way.

In Canada, social mapping has also been used to demonstrate Indigenous land use. In 1972 anthropologist Milton Freeman asked 1,600 Inuit residents of 34 different communities in the Northwest Territories to map their land uses. This allowed them to visually demonstrate their extensive engagement with and reliance on their ancestral lands. As Joe Bryan and Denis Wood write in “The Birth of Indigenous Mapping in Canada.” Weaponizing Maps: Indigenous Peoples and Counterinsurgency in the Americas, the maps were later used in “negotiations that enabled the Inuit to assert an aboriginal title to the 2,000,000 square kilometers of Canada now known as Nunavut” (Bryan and Wood, 64). They therefore played a key role in documenting Indigenous peoples’ attachments to land and communicating these attachments to a colonial system that sought to undermine them. Social mapping, therefore, not only documents peoples’ relationships to various places, but can also have the practical benefit of achieving justice for various communities.

Michael Donnelly, Sol Gamsu, and Sam Whewall, in their article Mapping the Relational Construction of People and Places produce a new mapping tool to capture geographic imaginaries of UK students. They use this tool “to understand the spatial and institutional hierarchies present in the spatial transitions of young people from home and school to university across the UK” (Donnelly et al, 93). Their method had two aspects to it. First, the participants would create the maps. “The research involved tracing the geographic movements of young people for university quantitatively, before seeking to understand qualitatively what lay beneath such patterning, in terms of cultural, social and economic factors at play shaping their geographic im/mobilities” (Donnelly et al, 94), write the authors. Then, the authors engaged the research participants in qualitative interviews to hear an in-depth account of their perceptions of space. Donnelly et al’s project “aimed to collect rich data on the meanings and significance attributed to different places and spatial locations within the UK” (Donnelly et al, 94).

In my own project, I used a similar method, though I combined the two steps taken by Donnelly et al. I asked Adin to draw a map of his sense of belonging on UBC campus before and after October 7th, 2023. As he drew, I asked him questions about his drawings, so that the mapping and the storytelling occurred simultaneously. In the end, I also asked him to clarify certain aspects of the map and to reflect on its absences (Leap, 208). Similarly to Donnelly et al, I wanted the exercise to “act as a creative means for participants to articulate their own socio-spatial imaginaries, not unduly framed by an external map-maker, which are made sense of through the interview process” (Donnelly et al, 106). For many Jewish, Israeli, and Zionist UBC students, the shock of the Hamas-led attack was superseded only by the nearly immediate unraveling of their campus. Many of them felt ostracized, villainized, and isolated. Recording visual depictions of their sense of belonging on campus, alongside their personal stories, can effectively communicate the extent of their struggles. These maps can then be used in conversations with university administration to advocate for support for these students, similar to Freeman’s efforts to communicate Indigenous peoples’ needs (Bryan and Wood, 64). This purpose is also similar to that of Donnelly et al, whose method “has the potential to account for how socio-spatial imaginaries can vary according to different geographic vantage points” (Donnelly et al, 95) and “is intended to be used in a comparative and relational way, comparing social groups across different locations, and capturing a broad understanding of the different locations occupied across social space” (Donnelly et al, 95). It can thus demonstrate which groups might have certain disadvantages in terms of using various spaces. In the case of Leap’s research, for example, his participants’ maps demonstrated the perspectives of gay Washington residents’ relationship with their urban environments. At UBC after October 7th, 2023, many Jewish, Israeli, and Zionist students have had a profound change in their sense of belonging on campus, which such maps can help articulate.

The Interview

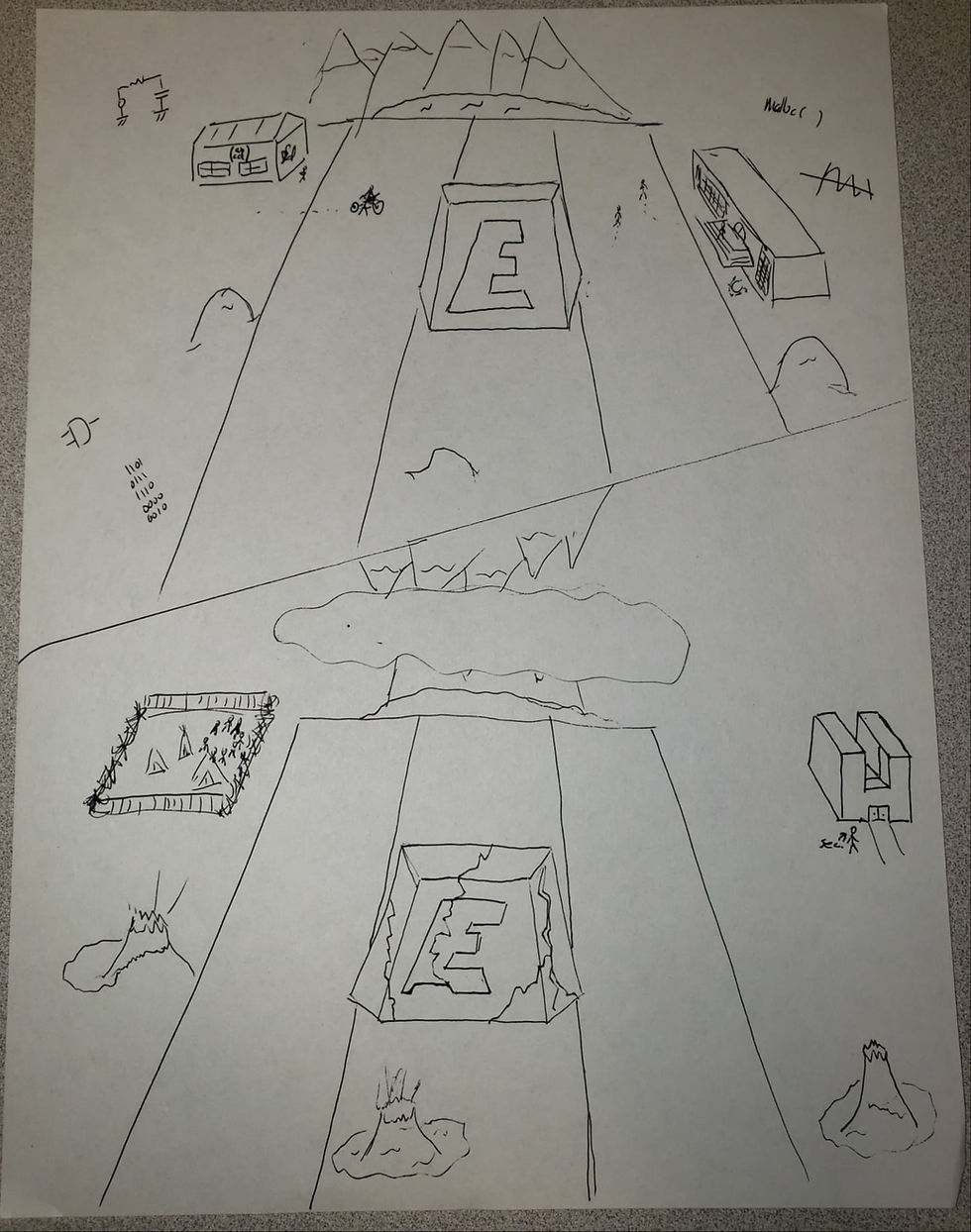

Adin and I meet at a coffee shop. I have already explained to him what I will ask him to do, but nevertheless, before beginning drawing, he sits in silence for a few minutes, gathering his thoughts. Then, he draws a slanted line across the middle of a paper, dividing it in two sections. The top is the Before, and the bottom is the After.

In the center of the Before section, he draws a large cairn with the letter “E” on it. “The Engineering cairn”, he explains. He says that before October 7th, he was on a really clear path. He was on track to finish his degree and his life revolved around Engineering. “People knew I was Israeli, but it wasn’t important”, he adds, foreshadowing what would come. His degree in engineering was the main part of his life, he explains. “It was straightforward and central”. Then, Adin draws the Math building. “It’s a place I’d enjoy taking courses”, he says simply.

Next, emerges the Main Mall, on which the cairn is placed. He explains that he would walk there sometimes between classes when he needed a few minutes’ break. In the background, he draws mountains. “As someone who didn’t grow up here, I was obsessed with mountains”. They envelop the campus, to which Adin adds another building. Irving K. Barber Learning Center. He explains that he used to spend a lot of time there, attending it for 1-3 hour study sessions two or three times a week. Smiling fondly, he recalls that his group of friends had a rigorous system for booking study rooms there. With seven of them, they would all take turns booking the rooms, which had to be booked far in advance, and rotate the people booking so that study spots were always guaranteed. Fading a bit, he says that though this study group still exists and regularly studies together, they have stopped inviting him. I ask why and he replies simply “because they think I’m a baby killer”. Though the reason was never explicitly stated to him, it is evident to him that some of the people in the group don’t want him to be a part of it anymore. He elaborates that the people in this group used to be good friends of his, but some of them erased him from their lives after October 7th.

Next, Adin draws a few small mounds all over the campus. I ask what those are, and he explains that they are “little dormant volcanoes”. “What erupts from them?”, I ask. “Hate”. He explains that there were people who were anti-Israel in his life in the past, but they were always able to have conversations about the conflict. Now, these people have cut him off. Adin says that he even used to speak with them in Arabic, one of the common languages of Israel that he picked up by living in it, and by taking a three month course years ago, while on an injury leave from the army. Though by that point he knew enough Arabic to get by, he wanted to learn more to be able to speak it. “It was important to me to understand people and speak to them in their own language”, he explains. Now, those opportunities have greatly diminished. As a few finishing touches on the Before map, Adin adds some people and engineering-related details. “Campus used to be a lively place” that revolved around engineering, he explains.

After reflecting on the “Before” for a while, Adin turns to the “After”. “Everything is darker”, he says bluntly, before he even begins to draw. He replicates the same structures and places, once again drawing the Main Mall and the Engineering cairn. The volcanoes have now erupted. I ask him what these eruptions symbolize. “The exposure of the hate. The masking off of the bias and ignorance. The emboldenment of the people who hate. And it’s spreading. It’s a constant presence, like a minefield. It could be anywhere”. What emerges is an environment completely penetrated by hostility. Adin then explains the story of his return to campus in January, 2024. He recalls giving his talk at Hillel and the talk being protested. The outpouring of hate he received was so strong that he was advised to have a security guard with him at all times on campus. Being accompanied by a security guard removed his sense of belonging. “My sense of belonging got lost”, he says. For two months, he explains, he would only walk around with one earbud in, constantly on alert and noticing people noticing him. In every space he was, he would note the security exits. The campus stopped feeling comfortable for him. “I want to leave”, he says softly. “There are good things, but the main feeling is bad”. He had to accept that at any moment, something bad will happen.

The only space where Adin could feel comfortable and like he could express himself was Hillel. He sketches it in the “After” section and I ask him why it doesn’t exist in the “Before”. “It wasn’t on my radar”, he says simply. Though he was aware of it, it was by no means central to his life, not nearly as much as Engineering. Now, it is the only place where he can express who he is as a Jewish-Israeli, Hebrew-speaking person. “It was the only place that supported me”, he says, reflecting again on the time after his talk prompted him to receive hate. He adds that the university administration did not support him during that time, and neither did any of his professors. He speaks fondly of the UBC Engineering advising team, who “saved him and went above and beyond” in helping him get through that time. In terms of campus spaces, Hillel was the only place that cared for him - the staff, but also the other students there. Adin points out that Hillel should probably be bigger, because it has become the center of his life on campus. In an ironic tone, he points out that it is not actually a university building, but a separate entity that some people are trying to shut down. Then, he adds a security guard outside of it. When I ask him why he did so, he explains that there is always a security guard there. “Why is there always a security guard there? I don’t know”, he laughs bitterly.

Adin continues drawing and adds cracks to the Engineering cairn. “The earthquakes cracked everything”, he explains, alluding back to the volcanoes and to how pervasive they were. “What was central to me before is no longer central”, he explains. I ask him what is central now. “Finishing and getting out of here”, he says bluntly. He adds a large cloud over the mountains. The Before was a beautiful day, he explains. The After is a grey, ugly day.

Then, Adin draws the encampment that took place in the spring and summer of 2024, when a group of students barricaded a public soccer field on campus and set up an encampment on it. I ask him why he chose to include it, and he explains that it’s because they occupied space and, for him, represented hate. “They used it to gather and educate people”, he says, adding that though the encampment is no longer there, the group continues to gather in other places on campus and spread the same information. He draws a barricade along the perimeter of the encampment and explains that it was “surreal”. “It was a space I wasn’t allowed in because of who I am”. Adin reflects on the irony of this encampment occurring within an Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion culture. This culture, he adds, constantly tells everyone that “you should never be vilified for who you are”. “What happened to that?”, he asks redundantly. Adding to this, he notes the lack of a moral compass from the university administration when dealing with the encampment, and its failure to push back against the hateful rhetoric that came out of it. He hastily clarifies that he doesn’t mean that the conflict should not be talked about. What he means is that these talks don’t have to include legitimizing violence and hatred against Jews.

With that, Adin’s maps are finished. We sit in silence for a while. I ask him why the people he drew in the Before map are missing from the After map. He explains that campus used to be lively and now there’s just a small group of people that cares about him. He lost a lot of trust in people, he explains, and lost so many good friends that that paints his entire sense of belonging at UBC. “There should be something upside down on this map”, he says, explaining how his whole world feels upside down now. He adds some upside down mountains to the top of the After map.

“People don’t know how bad it is”, he says, his voice hollow. He reflects on how pervasive the villainization and isolation have been. How he has come to anticipate hostility everywhere. How he has lost friends. How people who used to be his friends have tried to get other people to stop talking to him. How all of this has resulted in a never-ending behaviour pattern of him having to hide who he is for fear of retaliation and abuse.

Adin’s voice cuts off. His hands are shaking and there are tears on his face. He presses his hands to his eyes, breathing deeply. Poking out of his jacket sleeve, on his wrist, are two bracelets that read “BRING THEM HOME”.

Discussion

Adin’s identity as a “Jewish-Israeli, Hebrew-speaking person”, and, as some people on campus refer to him, “the IDF soldier”, is central to his diminished sense of belonging at UBC. His ironic reflection on the abundance of EDI culture during which his ostracization has occurred demonstrates this. He notes that in this culture, people are constantly reminded that “you should never be vilified for who you are”, and his rhetorical question “what happened to that?” underscores that this is exactly what is happening to him. His identity, and others’ hostile reactions to it, are therefore central reasons for his isolation and lack of belonging on UBC campus. Reflecting back on the time before October 7th, Adin explains that “people knew I was Israeli, but it wasn’t important”, underscoring that this part of his identity had never really had an effect on his interactions or his sense of belonging in the past. Since then, however, it became central to his diminished sense of belonging and has even become the reason for him being refused access to some spaces on campus. Reflecting on the encampment that took place on a public field at UBC, he recalls that its members barricaded its perimeter and barred access to it. “It was a space I wasn’t allowed in because of who I am”, Adin recalls, illustrating how central his identity was to this denied access, and diminished sense of belonging.

Hillel House emerged as the only place on campus where Adin could feel comfortable and like he could express himself. Though before October 7th it was not very important to him, after October 7th it was the only place on campus that supported him and where he felt like his identity was welcome. Through Hillel, directly or indirectly, he was able to find a group of friends that cared about him, which was so essential as so many of his friends abandoned him. At the same time, his fond feelings for Hillel are penetrated by feelings of worry, as Adin reflects on other students’ efforts to end its lease and on the constant presence of a security guard outside of it, necessitated by some students’ hostility toward it. These overlapping feelings indicate that while Hillel is an indispensable space for Jewish, Israeli, and Zionist students, these students’ feelings of belonging there are still interrupted by feelings of being unsafe and precarious.

Belonging on campus elicits negative emotions for Adin and the indications that he is unwelcome are extremely pervasive. The contrast in weather in the two maps also underscores the emotional connotation of both worlds. Whereas the Before map is a “beautiful day”, the After map is a “grey, ugly day”, reflecting Adin’s sense of isolation, emotional anguish, and diminished sense of belonging. When speaking about the time before October 7th, Adin uses positive emotions, smiling fondly at memories of his group of friends booking study spaces and studying together and attending lectures in buildings he liked. Reflecting on the time after October 7th, however, and in particular after his talk at Hillel, when things got so bad that he had to be accompanied by a security guard and be on constant alert, he recalls that he had to expect something bad to happen at any moment. “There are good things, but the main feeling is bad”, he remembers of that time. The negative emotions came to almost entirely paint his experience at UBC. Adin’s visceral reaction at the end of our interview demonstrates the extent of his anguish. Reflecting back on how his world turned upside down and how his sense of belonging vanished caused his hands to shake and tears to appear on his face. Strong negative emotions are attached to reflections on his sense of belonging now, a stark contrast to the past, when I did not matter much to him at all.

Prior to October 7th, 2023, Adin had not thought much about his sense of belonging. Reflecting back on it, he felt at home at UBC, and his belonging revolved predominantly around his sense of identity as an engineering student. The Engineering cairn’s large size and central placement on his “Before” map, as well as the inclusion of engineering-related spaces and symbols indicate that his degree was central to his sense of belonging at UBC. Adin explains that he had “a nice, simple life”, before. After October 7th, however, everything changed, and the notion of belonging became central for him, in that he felt regular signals that he does not belong. His feelings of being unwelcome and unsafe on campus illustrate this, as does his goal of “getting out of here”, which indicates that his sense of belonging at UBC has vanished.

Intriguingly, though Adin had never thought much about his sense of belonging at UBC in the past, he chose to draw dormant volcanoes in his Before map, which, in the After map, would explode and symbolize hate, bias, and ignorance. Adin explained that if he were to draw a map of his sense of belonging at UBC before October 7th, it would never occur to him to include these volcanoes, because he simply never knew that they were there. In retrospect, however, he felt it was important to include them, to trace their roots back and emphasize that they were always there. This looking back indicates that Adin has traced the enormous changes back to their inceptions and has tried to make sense of his new reality by looking for clues in his past. Adin seems to attempt to make sense of the changes in his life by looking at indicators in previous relationships, which he used to signify as friendly, but which have now turned volcanic and have eliminated his sense of belonging at UBC. This retrospective attempt to trace back his current conditions also indicates how central belonging has become for Adin, as his world turned upside down.

Conclusion

The interview process with Adin was very straightforward, but incredibly emotionally charged. Talking about belonging seemed to come naturally to him, there was very little doubt in what he said, which indicated that he has been thinking about belonging regularly, as it has become central to his life. At the same time, talking about belonging elicited strong emotions from him - the conversation ended in an intense reaction that was hard for him to contain. For Adin, his diminished sense of belonging prompted an adaptive response, which is demonstrated in him turning to Hillel House to cultivate a new sense of belonging. As his previous source of belonging - identity as an engineering student - diminished, he located Hillel House as a newfound source of belonging. He came to refer to Hillel as the only place that supported him and where he could express himself freely. This indicates that a sense of belonging is incredibly important to Adin, and that Hillel House plays a vital role in supporting Jewish, Israeli, and Zionist students on campus, even while it is perceived as precarious.

Belonging emerged as a dynamic, layered process, mirroring Yuval-Davis’s definition of the term. In Adin’s case, belonging was almost entirely affected externally and dependent on complex global events and reactions to them by people on campus. As he became a target of hate and ostracization, his perception of the campus completely shifted, so much that his world felt upside down, completely diminishing his sense of belonging. His experience underscores others’ abilities to impact belonging, expanding its dynamic nature to include external influences, which, in Adin’s case, proved incredibly powerful. It demonstrates the severe levels of isolation experienced by a Jewish, Israeli, and Zionist person on UBC campus, who, after October 7th, 2023, found himself a target of hostility.

Adin’s map shows his isolation, the severely diminished opportunities for social interaction, and the importance of Jewish, Israeli, and Zionist spaces. Powerful visual depictions of these experiences can spearhead the change needed to convey different communities’ relationships with space and articulate steps needed to reach meaningful resolutions for these communities. In the case of Jewish, Israeli, and Zionist UBC students, social maps of their sense of belonging on university campuses can communicate the impact that October 7th and reactions to it have had on their sense of belonging and the subsequent isolation they have come to experience. These maps can then be leveraged to advocate for meaningful change for these students as they navigate their upside down world.

Works Cited

Baxter, David. 2024. “Antisemitic Incidents Rose in Canada Last Year — and after Oct. 7: B’nai Brith.” Global News. May 6, 2024. https://globalnews.ca/news/10476939/anti-semitism-bnai-brith-canada/.

Bryan, Joe, and Denis Wood. “The Birth of Indigenous Mapping in Canada.” Weaponizing Maps: Indigenous Peoples and Counterinsurgency in the Americas, The Guilford Press, New York, 2015, pp. 54–73.

Chaudhry, Aisha. 2024. “Protestors Gather at Buchanan, Boycott Class and Demand Divestment.” The Ubyssey. 2024. https://ubyssey.ca/news/protestors-gather-at-buchanan-boycott-class-and-demand-divestment/.

Donnelly, Michael, Sol Gamsu, and Sam Whewall. 2019. “Mapping the Relational Construction of People and Places.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 23 (1): 91–108. doi:10.1080/13645579.2019.1672284.

Lewin, Ellen, and William Leap. 2009. Out in Public : Reinventing Lesbian/Gay Anthropology in a Globalizing World. Chichester, U.K. ; Malden, Ma: Wiley-Blackwell.

Little, Simon. 2024. “UBC Student Union Rejects Proposed Referendum on Evicting Hillel House.” Global News. March 2024. https://globalnews.ca/news/10327028/ubc-hillel-referendum/.

Little, Simon, and Emily Lazatin. 2024. “Pig Head Mounted on UBC Fence an Act of Antisemitism, Jewish Group Says.” Global News. September 6, 2024. https://globalnews.ca/news/10735148/ubc-antisemitism-concerns-pig-head/.

Rochefort, Renée. 2024. “Hillel BC Event Featuring IDF Soldier Draws Protests.” The Ubyssey. 2024. https://ubyssey.ca/news/hillel-bc-event-featuring-idf-soldier-draws-protests/.

Ruttle, Joseph. 2024. “Anti-Israel Graffiti Greets Professor Visiting UBC from Jerusalem University.” Vancouversun. Vancouver Sun. October 23, 2024. https://vancouversun.com/news/anti-israel-graffiti-ubc-jerusalem-professor.

“The University of British Columbia - U15 Group of Canadian Research Universities.” 2023. U15 Group of Canadian Research Universities. November 2, 2023. https://u15.ca/members/the-university-of-british-columbia/.

Yuval-Davis, Nira. “Belonging and the Politics of Belonging.” Patterns of Prejudice, vol. 40, no. 3, 2006, pp. 197-214, doi:10.1080/00313220600769331.

Comments